Sacrificial anodes – understanding the importance of anodes on boats

Revised by Hans Karlsson, Corrosion engineer with 30 years of experience within the cathodic protection industry .

Whenever you have two distinct metals that are physically or electrically associated and submerged in seawater, they turn into a battery. A small amount of current streams between the two metals.

The electrons that make up that current and flow are provided by one of the metals surrendering bits of itself- as metal particles – to the seawater. This is called galvanic corrosion and, left unchecked, it rapidly decimates submerged metals.

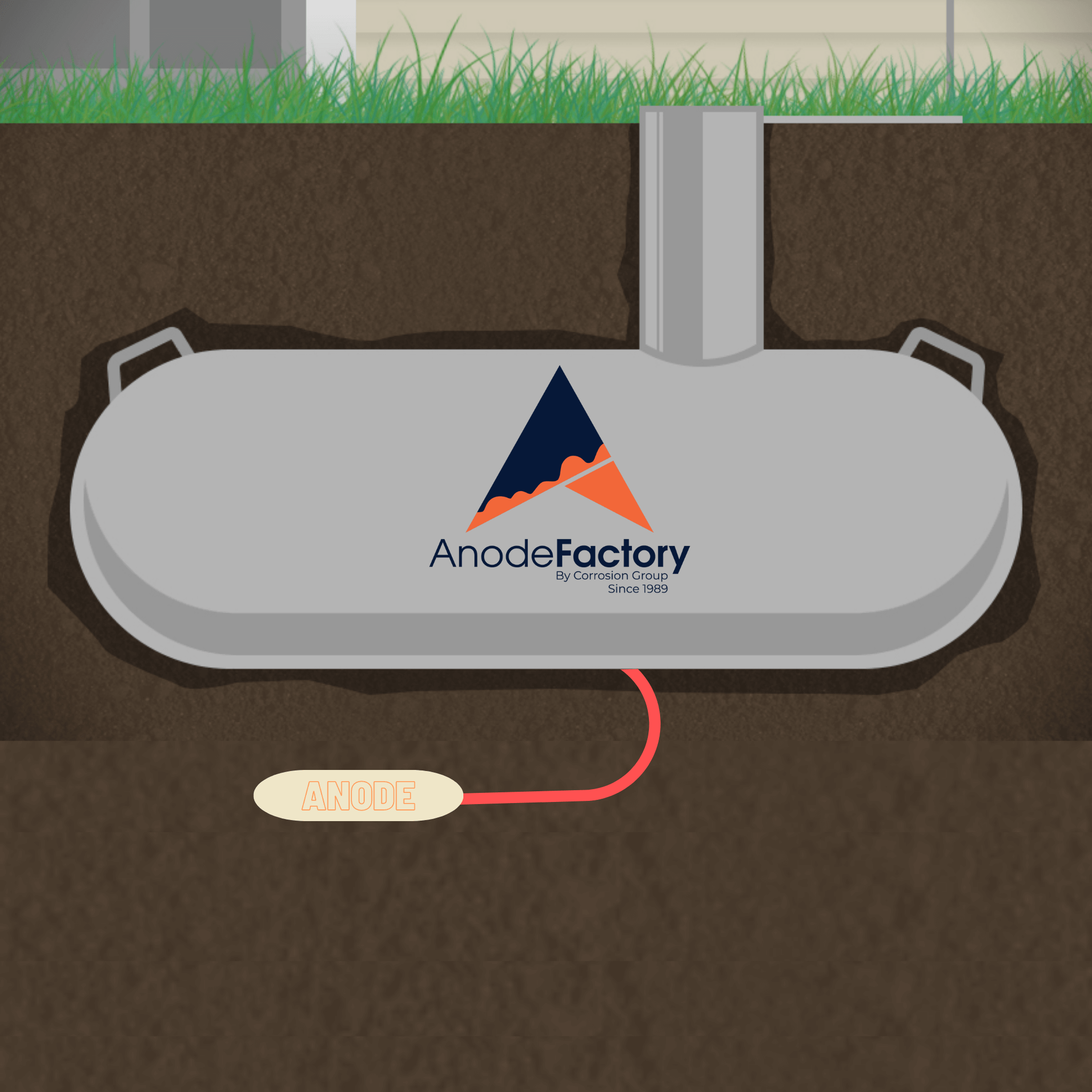

The most well-known loss to galvanic corrosion is a bronze or aluminum propeller on a stainless steel shaft, however metal struts, rudders, rudder fittings, outboards, and stern drives are likewise in danger. The way we check galvanic corrosion is to include a third metal into the circuit, one that is less noble than the other two to surrender its electrons.

This bit of metal is known as a sacrificial anode, and frequently it is zinc (usually in brackish waters/seawater), aluminum (usually seawater/brackish water) or magnesium (usually brackish water or freshwater).

It is difficult to exaggerate the significance of keeping up the anodes on your vessel. At the point when an anode is missing or to a great extent squandered away, the metal segment it was introduced to secure starts to break up – guaranteed.

Go to Zinc anodes, Magnesium anodes, Aluminum anodes